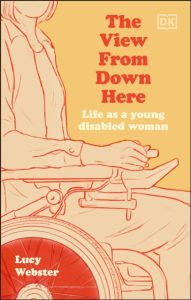

What is life like when you’re young, female, and disabled? Lucy Webster is a journalist who is herself disabled, and she’s a powerful accessibility advocate. Now she’s brought together her experiences in her memoir: The View from down here: Life as a young disabled woman.

What is life like when you’re young, female, and disabled? Lucy Webster is a journalist who is herself disabled, and she’s a powerful accessibility advocate. Now she’s brought together her experiences in her memoir: The View from down here: Life as a young disabled woman.

Here are some glimpses of her experiences:

- The dating agency who refused her membership on the grounds “We have never had success with a wheelchair user”.

- The Clapham club whose bouncer blocked her with the words “We can’t let you in with a chair”, and, when challenged, doubled down with the argument that it was busy and they couldn’t keep her safe.

Anyone who is paying attention will have seen, and been appalled by, such horror stories before. For me, though, the value of this memoir lies in its painful recording of the more mundane, day-to-day realities of life ‘down here’. It was a surprise to learn, for example, that this confident, articulate, compelling writer had been forced to abadon cleaning her own teeth because her wayward body means that she can’t do that everyday task without hurting herself.

I shared my copy of the book with my friend Jane Matthews, who is the author of The Carer’s Handbook. She said “Until I read The view from down here, it hadn’t occurred to me how fundamentally the need for living with a full-time carer changes every aspect of daily life – recruiting, training, retaining, and actually living with someone you rely on for everything from brushing your teeth to getting you to bed at night”.

It hadn’t occurred to me how fundamentally the need for living with a full-time carer changes every aspect of daily life

Jane Matthews reacts to Lucy Webster’s book

By the time Lucy Webster was 18, she had to learn how to be an employer (to her carers), as well as how to manage the dynamics in this most complex of relationships. She writes: “Allowing someone to do your care is more an act of faith than of delegation; you are trusting someone with absolute control of your health and wellbeing without any knowledge of whether they deserve that trust.”

Jane and I both consider ourselves to be accessibility advocates and feminists. For example, we are acutely aware of the pressures on women to have children. But we both realised, reading this book, that we had overlooked the need to stand with those disabled women facing the opposite assumptions: about their ability, and right, to be mothers. Webster was 28 before she learned that having children was a possibility for her; up to that point no-one who’d heard her talk wistfully about wanting to be a mother ever considered their responsibility to have a conversation with her about how this might work.

In a truly equal world, feminists would campaign for all women, she argues: “Where is the outrage about the forced sterilisation of intellectually disabled women? Where are the campaigns to make sex and pregnancy education inclusive of disabled women? Where are the protests demanding disabled mothers receive adequate social care or against the extraordinary rates at which disabled parents lose access to their kids?”

Where are the campaigns to make sex and pregnancy education inclusive of disabled women?

Lucy Webster, The view from down here

Ableism overlaid with sexism are the twin lenses through which this moving and shocking memoir lays out the need for awareness and change in every area of life, education, work, friendships, body image, dating and motherhood. It is an uncompromising read which left me asking ‘why didn’t I know that?’ and ‘what are the ways in which my own choices and behaviour are a part of the problem?’

Above all, what do we need to do, to say and to change? Because what Lucy Webster’s memoir requires of readers is that we join her in understanding discrimination as a social model: a choice we make to discriminate in favour of non-disabled people and against disabled people; which is based on the invisible assumption that some lives are less valuable than others.

She concludes: “If you care about equality, you should care about ableism.” And a good way to care would be to read this book.