‘Numbers and Nerves: Information, emotion and meaning in a world of data’ is an eclectic collection of chapters exploring the difficulties many of us have making sense of large numbers. In an age when we are bombarded with facts, statistics and overwhelming numbers, how are we to understand their meaning?

‘Numbers and Nerves: Information, emotion and meaning in a world of data’ is an eclectic collection of chapters exploring the difficulties many of us have making sense of large numbers. In an age when we are bombarded with facts, statistics and overwhelming numbers, how are we to understand their meaning?

The book was first published in 2015, and I recently re-read it. I found it even more compelling second time around, and realised that I really wanted to review it as I still found plenty that is relevant 10 years after publication.

The editors are Scott Slovic and Paul Slovic. Their shared surname is no coincidence: Paul Slovic coined the expression ‘psychological numbing’ to describe the way humans find it easier to connect with the particular than with the general, and the book arose from conversations with his son Scott that connected their two fields and common interests.

- Numbers and Nerves: information, emotion and meaning in a world of data

- Scott Slovic, Distinguished Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Idaho

- Paul Slovic, Professor of Psychology at the University of Oregon

Psychological numbing is necessary and problematic

‘Psychological numbing’ is the human necessity of diminishing the effects of overwhelming events or information.

The book is full of the practical effects of psychological numbing, quoting research such as people being less likely to send money to provide life-saving water to a refugee camp when the camp is large rather than when it is small.

When calculating in accord with psychophysical principles, one life plus one life is valued more than one life but less than two lives”.

Numbers and nerves chapter 2 ‘Pseudoinefficacy and the arithmetic of compassion’ (Daniel Västfjäll, Paul Slovic, and Marcus Mayorga)

Campaigners and fundraisers ‘need a Darfur puppy’

The iconic example of our failure to connect with numbers is in a chapter ‘The Power of One’ by Nicholas Kristof, a version of his New York Times editorial originally published under the title ‘Save the Darfur Puppy’. He argues that in a situation as complex as genocide people may be more moved by the plight of a single puppy than by the suffering of many individuals. The Darfur genocide was at its height in 2003-2005. The Masalit and related peoples targeted then are still suffering.

- “Save the Darfur Puppy’ 2007 editorial by Nicholas Kristof (New York Times paywall)

Other chapters in the book’s first section delve into the research around this, illustrating how fundraising campaigns focused on a single individual do better than those trying to raise awareness of the plight of millions.

Contributors include naturalists and artists

At a time of genocide in Gaza, of climate emergency and huge disparities of wealth, we often can’t understand the significance of the figures we are reading, which then makes it harder to respond. These issues are not new and I found myself especially interested in the chapters describing how artists are trying to help us better connect with the massive numbers that are a part of the world we now live in.

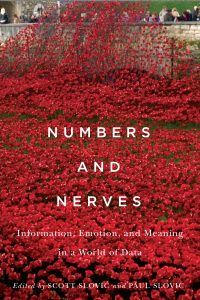

One of the ways in which we can be helped to make sense of big numbers is through visualisation. The book’s striking front cover features the 2014 installation of a sea of ceramic poppies surrounding the Tower of London, and was conceived by Paul Cummins and staged by Tom Piper to represent servicemen killed in the First World War. Their artwork helped an estimated five million visitors – including me – to understand more about the scale of the slaughter.

The book is inspirational for anyone working in quantitative research

As qualitative and quantitative researchers we are always thinking carefully about the stories our data is telling, and how we can use the numerical information to accurately represent what is going on. This book adds another dimension to our work, reminding us that people think and understand best when numbers and nerves work together.

The final part of the book concludes with a selection of interviews, in which professionals share their experiences and strategies in communicating “difficult data”. As someone with mild dyscalculia, this section in an interview with Chris Jordan conducted by Scott Slovic especially resonated with me.

Chris: … the human mind can’t comprehend numbers beyond more than a few thousand. Recently I heard that there’s another guy out there who says we can’t comprehend more than about seven. As soon as you start getting into twenty-two or forty or sixty or something like that, you have to think in groups. That’s two groups of ten, six groups of ten – but seven is the biggest number we can really feel in our hearts

Numbers and nerves chapter 16 ‘Introspection, Social Transformation and the Trans-Scalar Imaginary: An interview with Chris Jordan by Scott Slovic

Chris Jordan created a series of artworks that explore very large numbers of items that have a collective impact on modern life. For example, a thumbnail on his website looks like a hazy picture of a ship sinking, with large window that shows that the image is ‘Unsinkable, 2013 60×107 (152x272cm) Depicts 67,000 mushroom clouds, equal to the number of metric tons of ultra-radioactive uranium/plutonium waste stored in temporary pools at the 104 nuclear power plants in the US (2013 statistic).’

- Chris Jordan Running the numbers: Portraits of Human Mass Culture (best viewed on desktop)

I know that I do not have the resources, tenacity, or imagination to create an image from 67,000 mushroom clouds, or the 106,000 aluminium cans in another of Chris Jordan’s works. But I came away from reading these chapters with a mind buzzing with ideas about how to approach the numbers and to create context for them within my professional practice.