In this blog post we will help you to decide how to use the time you have with trainees to run a realistic and effective training course.

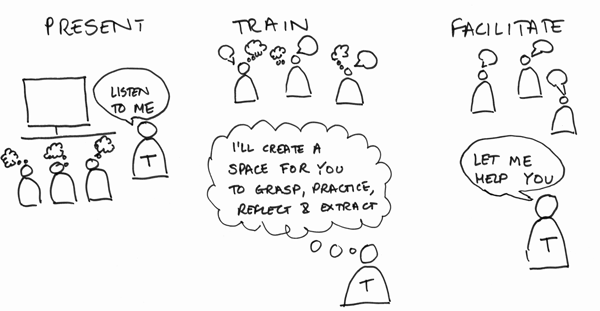

We work as trainers ourselves, and we help new trainers to develop their courses. Training is different to presenting, and has elements of facilitating. We believe that effective training gives attendees the opportunity to grasp, practice and reflect on new ideas – and then extract useful parts of those ideas to apply.

Caroline was working with a new trainer who proudly tested a training module with a target time of 15 minutes.

The new trainer spoke for 12 minutes and then allowed 3 minutes for questions. The ideas at the beginning of the 12 minutes had faded from the attendees’ minds and they didn’t know where to begin with their many questions.

The trainer had created a presentation, not a training course.

Your time allocation must allow for four phases

Good learning experiences take time. In order to retain and make use of an idea from your training course, allow attendees to work through four phases:

- Grasp enough about the idea in order to be able to practice it

- Practice using the idea

- Reflect on the practice and the idea

- Extract useful parts of the idea to apply to their own context.

A presentation focuses entirely on the ‘grasp’ part and leaves it up to the attendees to do the other parts on their own.

Clara took over a training course that was getting feedback such as:

-

- “Some more exercises would be good”

- “Too much getting talked at”

- “Not as immersive as it should be”.

After Clara re-designed the course to include more exercises and reflection, she regularly got feedback such as:

-

- “Good mix of theory and exercises”

- “Activities a good length plus right level”

- “Activities stimulated you to think”.

A good training course contains just a few good ideas

We think of a training course as being made up of several ideas, and that’s what we are going to focus on in this post.

Caroline’s typical training course is a 90-minute workshop, usually with about four to six ideas in it. For example, an ‘idea’ she might teach in a survey workshop could be ‘In a Likert item, the question statement is more important than the number of response options’.

Clara’s typical training course is a 10-hour online course broken into four 2.5 hour sessions. She will generally have three or four big ideas in a course. For example, an ‘idea’ she teaches might be ‘As people who create services, it’s in our power to either exacerbate inequities, or to address them’.

We have come to accept that we will never be able to cover everything in a training course. If our attendees take away two or three ideas from the training, or even just the confidence to apply one idea to their work immediately, then that’s a good result.

Allocate some time to get started and to close the session

We also need to allocate some time to getting started and to closing, so that an overall plan looks like this:

- People arrive and assemble

- Welcome and introductions

- [One or more ideas]

- Wrap-up and closing.

In her 10-hour online training Clara will generally allow 30 minutes for arriving, welcoming, acknowledgements, introductions, a code of care, reviewing the agenda and asking attendees what they want from the course in the first session. She makes time to set the tone and hear each person speak aloud, as often they won’t have met before. Then she allocates 5 minutes at the start of the other three sessions for arriving and assembling. At the end of each of the four parts, Clara leaves 5 minutes to summarise and invite feedback, and at the end of the whole course Clara will take 15 mins to ask attendees to reflect on their biggest takeaways, leave feedback and say thanks and farewell to each other. That gives her 8 hours and 50 minutes in total for ideas.

Caroline is often working with attendees online for 60 minutes. She’ll generally allow about 5 minutes for the “arrive and assemble” part because of the need to start online tools and move across from a previous meeting. Often attendees all know each other, so she will only allocate a minute for them to put their names, job titles, and locations in the chat. At the end of the session, she may use an online tool such as EasyRetro for another 5 minutes to give attendees a chance to capture their overall reflections. That gives her 50 minutes for ideas.

Do the necessary background

Before you can plan your time within a training course, you need to know:

- who your trainees are, what they already know, and what they want to learn

- how long you will have with your trainees

- a sense of what you want them to take away from the training – these are the ‘ideas’.

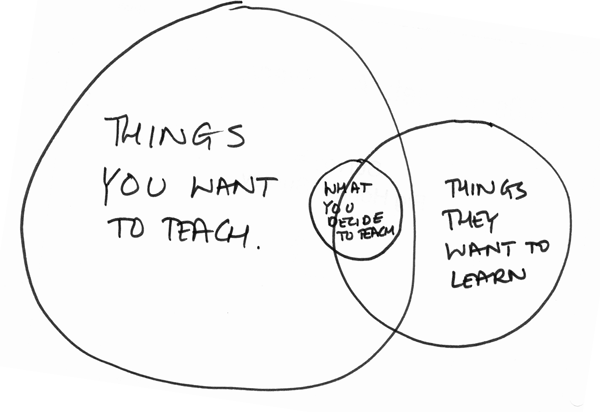

Sometimes the ideas you want to include conveniently line up with ‘what they want to learn’, but more often you’ll do some thinking about how to ensure that the trainees get what you consider they need as well as what they think they need.

Find the size of each idea you want to cover

In theory, you can do any idea in any amount of time by adding in details or cutting them out.

Both of us can easily recall training sessions where we felt that the trainer had gone into more detail than was appropriate for the training course.

Caroline saw this example in a newsletter from Simon at Scribbler’s Calligraphy:

“…The content was excellent, but the presenter spent the first hour telling us everything we’d be able to do by the end of the day. While that optimism had its place, we didn’t get stuck into the useful stuff until much later – by which point, I was tiring.”

Conversely we can also recall training courses where there hasn’t been enough detail to allow us to grasp and apply the ideas.

A lot of our preparation time goes into working though the balance between the level of detail for each idea and the time we have available. Sometimes we have to make the tough decision to sacrifice a whole idea because it just won’t fit.

If you’re not sure whether you’ve got the balance right, the best way to find out is to create some training and try it out with someone.

A new trainer wanted to cover the topic “how to write a good survey”, but was only given a 15 minute training slot. Caroline encouraged her to choose a much smaller idea: “how to write a good survey invitation”, which was manageable in 15 minutes and will definitely be useful to the audience of people who need to learn how to write good surveys.

Neither of us could think of any example where we were given more time than we could fill for a training course. We are reconciled to the fact that we will never be able to ‘cover everything’.

Allocate time to grasp, practice, reflect, and extract

We break up the time we have for each idea into the four phases:

For a small idea, taking 15 minutes, we would have:

- 5 minutes talking about it (‘chalk and talk’) – this is ‘grasp’ the idea

- 5 minutes to do an exercise – this is ‘practice’

- 5 minutes to discuss the exercise – the opportunity to ‘reflect’

- A brief single slide with a takeaway point – a shortcut to ‘extract’.

For a bigger idea, taking 45 minutes, we would have:

- 5 minutes talking about it – ‘grasp’

- 20 minutes to do an exercise – ‘practice’

- 10 minutes to ‘reflect’, for example by putting thoughts in a chat or retro

- 5 minutes for a small extra exercise that might be asking attendees to pair up to compare their reflections – half of the ‘extract’ phase

- 5 minutes for everyone to talk about what they learnt and wrap up the exercise – the rest of the ‘extract’ phase.

If we have more time, such as 90 minutes, we would rarely spend all this time on an individual idea. We would try to chop the idea up into smaller chunks. Aim for a maximum of 45 minutes because attendees need a break of some sort after about 45 minutes of training, and they need to re-group and get re-started after each break.

Clara noticed that the ‘reflect’ part of the training needs to happen within the same 45 minute chunk of time as the exercise. She’s learned that it’s very hard for attendees who are fully concentrating to recall their learning experiences from more than 45 minutes ago.

Don’t talk too much

You might notice that in our example timings above, the initial ‘talking’ bit is the same size, just 5 minutes long, for both the 15-minute and 45-minute ideas. Bigger ideas don’t require more talking, they need more time for people to think them through and try them out.

Vary the length of the exercises

Variety is more fun for you and the attendees. By adding short exercises and longer ones, you’ll help attendees stay engaged.

A few short exercises that we use regularly include:

- A speedy little poll (Answer yes/no/don’t know/something else) to help attendees to think about your content

- “Pop in the chat the last time you … ” or “write a post-it note about…” both work to keep people thinking, and are quick individual exercises

- In breakout rooms or in-person training, “share … with your neighbour” can help attendees to start chatting to each other.

If you have only planned short exercises, think about adding something that’s more in-depth and challenging. A longer exercise which people do in groups can help them to engage with an idea and work through a problem together.

Clara runs a course where she puts trainees into groups and asks each group to spend 20 minutes filling in a template with multiple sections. Trainees need time to absorb the details of the template, and they get a lot of value from comparing their thoughts about those details with each other.

A longer training course often benefits from a longer exercise

If you have a half day or whole day to work with, it’s good to allow time for a longer exercise that trainees can really get their teeth into.

For example, some approaches we might take within the day are:

- spend 5 minutes on theory, 15-20 minutes on an exercise and then 10 minutes debriefing

- spend 1-2 minutes on asking people to reflect on experience first as individuals, then compare experiences in pairs for 5 minutes, then work together as a big group for 10 minutes to generate a summary of what they already know

- set aside 90 minutes for a much longer exercise but break it up into smaller chunks to guide people through it.

When Caroline is teaching a survey design course in-person for a whole day, she allocates an entire 90-minute session to getting teams to create and test a draft questionnaire. She breaks the session into five roughly equal tasks:

-

- recap on previous work on goals and sampling,

- write questions,

- draft a questionnaire,

- create an invitation and thank-you, and

- test the invitation, questionnaire, and thank-you.

Allow for thinkers and talkers

Some people prefer to spend time thinking on their own, others prefer to talk about things with others. Some people like a mix of both.

You may have noticed when we were talking about longer exercises, we suggested one that we often run in three steps:

- ask everyone to spend a minute on their own jotting down their first thoughts individually

- then get them to work in pairs to share and compare their thoughts

- then ask the pairs to combine in teams and have a wider discussion.

These steps give the ‘think on their own’ people the space at the start to gather their thoughts. The ‘talking together’ people will be a little bored, but only for a minute. When everyone gets to the ‘combine in teams’ part, the people who prefer to think on their own can allow the ‘talk together’ people to do more of the work. This is similar to the Liberating Structures method called “1-2-4-All” and the teaching method called Think-Pair-Share.

Allow for people to process information in different ways

We have also noticed that some people like to hear information, some like to see it and some like to do something with it. For example, most people can write something down but some will really enjoy the chance to sketch instead or to make a mind-map. If you give people a choice, they can pick the one they prefer.

Test your training

We both find that the first time we deliver a training course, it’s always a bit rough in places.

Even though each of us will invariably practice on our own and then again with a trusted colleague, it’s hard to replicate the experience of having a group of trainees in any other way than by having a group of trainees. We try hard to run a pilot course – with a larger group of colleagues, or by offering a discount course, to work out some of the wrinkles.

Caroline ran a course where her first exercise was an introduction to the main idea. She found that attendees needed to say hello to each other, and weren’t sure when to break off from greeting each other to move to the main idea part. Splitting the exercise into two shorter ones – one for greeting, and one to introduce the main idea – solved the problem.

Without a pilot, the first live course becomes a ‘live pilot’. It will have more stuff that just didn’t work as well as we hoped. Sometimes we are forced to accept that as the reality.

It’s OK because there is always something we can improve in the training every time.

Clara continues to improve her introduction to service design course even though she has been iterating and improving it for many years.

Caroline has taught writing for the web courses based on her website Editing that works since 2004. She always finds some way to improve them.

Be ready to adapt

A lot of the fun of training is that real people come with their actual ideas, experiences, and attitudes. Some groups will be chatty, others are not. Some arrive precisely on time and are great with technology, others are more relaxed. Sometimes an exercise runs as we expect, others it can take a totally different direction.

It’s good to have some flexibility. We’ve learned that you can cut almost anything from the ideas section and attendees will still have a good experience – but try really hard to keep the final wrap-up and close intact.

A good time plan relies on realism and practice

You can’t turn an hour’s training into 15 minutes of training by talking more quickly. Nor can you turn an hour’s training into 15 minutes of training by cutting out all the exercises. Instead, narrow down what you are trying to cover in the time.

Effective training allows attendees to grasp the idea, practice the idea, reflect on the idea and extract useful parts of the idea.

Find the size of each idea you want to cover.

Don’t talk too much.

Vary the length and types of exercises that you offer.

Practice your training before you run it.

Be ready to adapt.

Finally, enjoy the experience. We love working out how to share our ideas in training, and we love even more learning from our trainees because they always inspire us.

This post is also available on Clara Greo’s website. We’d like to thank Alistair Greo, Jane Matthews, and Khadijah Mohammed for their help with testing.