Have you heard that my book is available from Rosenfeld Media? Surveys that work: A practical guide for designing and running better surveys.

In the book, you’ll find a seven-step process for designing, running, and reporting on a survey:

- Goals

- Sample

- Questions

- Questionnaire

- Fieldwork

- Responses

- Reports

To ensure that the survey gets accurate results, I encourage you to think throughout about the errors that can occur, using a core concept from survey methodology: Total Survey Error.

And to get a flavour of what you’ll find in the book, here’s an excerpt. It’s part of the first step: Goals.

Chapter 1 — Goals: establish your goals for the survey

In this chapter, you’re going to think about the reason why you’re doing the survey. By the end of the chapter, you’ll have turned the list of possible questions into a smaller set of questions that you need answers to.

Write down all your questions

I’m going to talk about two sorts of questions for a moment:

- Research questions

- Questions that you put into the questionnaire

Research questions are the topics that you want to find out about. At this stage, they may be very precise (“What is the resident population of the U.S. on 1st April in the years of the U.S. Decennial Census?”) or very vague (“What can we find out about people who purchase yogurt?”).

Questions that go into the questionnaire are different; they are the ones that you’ll write when you get to chapter 3, Questions.

Now that I’ve said that — don’t worry about it. At this point, you ought to have neatly defined research questions, but my experience is that I usually have a mush of draft actual questions, topic titles, and ideas (good and bad).

Write down all the questions. Variety is good. Duplicates are OK.

Give your subconscious a chance

If you’re working on your own, or you have the primary responsibility for the survey in a team, then try to take a decent break between two sessions of writing down questions. A night’s sleep gives your subconscious a chance to work out what you really want to find out. If that isn’t practical, then maybe try a walk in the fresh air, a break to chat with a friend, or anything else that might provide a pause.

Get plenty of suggestions for questions

If you’re working with a team or you’re in an organisation, then often when word gets out that there’s a survey ahead, colleagues will pile in with all sorts of suggestions for their questions. This can feel a little overwhelming at first, but it’s best to encourage everyone to contribute their potential questions as early as possible so that you can carefully evaluate all of them, focus on some goals for this specific survey, and have a good selection of other questions available for follow-up surveys and other research.

If I’m too restrictive at the very beginning, I find that everyone tries to sneak just one little extra essential question into the questionnaire a day — or even an hour — before the fieldwork starts. By then, it is too late to test the little extra questions properly, and they could sink my whole survey.

But while you’re still establishing the goals for the survey? Great! Collect as many as possible. Encourage everyone to join in — colleagues, stakeholders, managers, whoever you think might be interested. If you’re running a workshop, give the introverts some space by having a bit of silent writing where everyone captures their individual question ideas by writing them down.

Create a nice big spreadsheet of all the suggestions, a pile of sticky notes, or use whatever idea-gathering tool works for you.

Ideally, make it clear that there’s a cutoff: suggestions before a particular date will get considered for this survey; miss the date, and they’ll be deferred until the next opportunity. This helps to encourage the idea of many Light Touch Surveys.

Challenge your question ideas

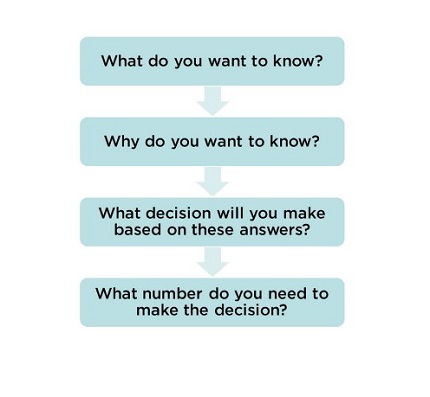

When you’ve gathered or created question ideas, it’s time to confront them with these four detailed challenges in Figure 1.2:

- What do you want to know?

- Why do you want to know?

- What decision will you make based on the answers?

- What number do you need to make the decision?

Ask: What do you want to know?

Surprisingly, I find that the question suggestions that I create or collect from colleagues often do not relate to what we want to know. Many times, I’ve challenged a question by saying “OK, so you’re thinking about <xxx question>. What do you want to know?” and it turns out that there’s a gap between the question and the reason for asking it.

Probably the most common example is the question: “Are you satisfied?” which is OK but very general.

Ask: Why do you want to know?

I’m usually working with someone else when I’m doing a survey. To help narrow down from ”every possible suggestion” to a sensible set of goals for the survey, I ask “Why do you want to know the answers to these questions?” and we then go on to challenge ourselves with the four questions in Figure 1.2.

If I’m on my own, then I find it helps to add “this time” or “right now” — to help me focus on the practical matter of getting my ideas down to something manageable. Come to think about it, that’s not a bad idea for a team, too — it helps all of them realise that they don’t have to ask everyone everything all at once.

Ask: What decision will you make based on the answers?

If you’re not going to make any decision, why are you doing the survey?

Look very hard at each of the suggested questions and think about whether or not the answers to them will help you make a decision.

Don’t worry at this stage about the wording of the questions, or whether people will want to answer them. You’ll work on those topics in upcoming chapters.

But if the answers to a question won’t help you make a decision, set it aside. Be bold! The question might be fascinating. You might be looking forward to reading the answers. But you’re trying to focus really hard on making the smallest possible useful survey. You don’t need to waste the question — it can go into the possible suggestions for next time.

At this point, you’ll have some candidate questions where you know what decisions you’ll make based on the answers.

Ask: What number do you need to make the decision?

In Chapter 0, “Definitions,” I emphasised that a survey is a quantitative method and the result is a number. Sometimes you’ll realise at this point that although you have candidate questions, you do not need numeric answers to them in order to make the decisions. That’s fine, but it also means that a survey is probably not the right method for you. Your work so far will not be wasted because you can use it to prepare for a more appropriate method

Choose the Most Crucial Question (MCQ)

If you were only allowed answers to one of your candidate questions, which would it be? That’s your Most Crucial Question (MCQ).

The Most Crucial Question is the one that makes a difference. It’s the one that will provide essential data for decision-making.

You’ll be able to state your question in these terms:

“We need to ask __________________.”

“So that we can decide________________”.

At this stage, don’t worry if it’s a Research Question (in your language, maybe even full of jargon) or the question that will go into the questionnaire (using words that are familiar to the people who will answer).

Test your goals: Attack your Most Crucial Question

Try attacking every word in your Most Crucial Question to find out what you really mean by it. Really hammer it.

Here’s an example: “Do you like our magazine?”

- Who is “you”? Purchaser, subscriber, reader, recommender, vendor, or someone else?

- What does “like” mean? Admire? Recommend? Plan to purchase? Actually purchase? Obsessively collect every edition? Give subscriptions as gifts?

- What do you mean by “our”? Us as a brand? A department? A team? As a supplier to someone else?

- What do you mean by “magazine”? Every aspect of it? The paper edition? The online one? The Facebook page? The article they read most recently? Some parts, but not others? Does it matter if they’ve read it or not?

I found a great attack on a question by Annie Pettit, survey methodologist. She starts with the question:

“When was the last time you bought milk?”

Here’s how Annie attacks “bought” and “milk”:

“Wait, do you care if the milk was purchased? Or could it be that we have an arrangement whereby we don’t actually pay for milk? Perhaps people who live on a farm with dairy cows, or people who own a convenience store?

Do you mean only cow milk? What about milk from goats, sheep, buffalo, camel, reindeer? Or what about milk-substitutes from nuts or plants like soy, almond, rice, coconut that are labeled as milk? Were you really trying to figure out if we put a liquid on cereal? “(Pettit, 2016)

(And she added a whole lot more about topics, like whether or not chocolate milk counts).

Decide on your defined group of people

When you’ve really attacked your MCQ, look back and think about your “defined group of people” — the ones who you want to answer.

Add them to your statement like this:

“We need to ask ____(people who you want to answer)____.

The question _____(MCQ goes here)___________.

So that we can decide___(decision goes here)_______.”

If your defined group of people is still vague — “everyone” or something equally woolly — then try attacking again. A strong definition of the group you want to answer at this point will help tremendously when you get to the next chapter, Sample.

But before you proceed to Chapter 2, let’s pause for a moment and think about your plans.

Check that a survey is the right thing to do

Is your research question something that you must explore by asking people, or would it be better to observe them?

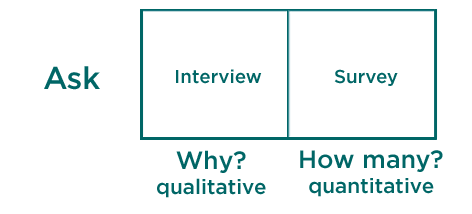

Do you want to know “why?” — qualitative — or “how many?” — quantitative?

Let’s look at this definition again:

A survey is a process of asking questions that are answered by a sample of a defined group of people to get numbers that you can use to make decisions.

I’m going to contrast that with this definition:

An interview is a conversation where an interviewer asks questions that are answered by one person to get answers that help to understand that person’s point of view, opinions, and motivations.

Both of them rely on asking: the interview is about “why” — qualitative — and the survey is about “how many” — quantitative, as in Figure 1.3

That’s all for the moment

This excerpt was originally published by Lou Rosenfeld on Medium. I hope you’ll want to read more from the book, so please get your copy of Surveys That Work!